Solitons are localized wave disturbances that propagate without changing shape or spreading out. This remarkable effect depends on a self-attraction either created by the medium the solitons propagate in, or in the case of “bright” solitons, a self-attraction of the wave itself. If the self-attraction increases with the size of the wave amplitude, solitons with larger amplitude are “squeezed” harder to keep them from spreading out, while smaller amplitude, broader solitons require a gentler squeeze. Solitons have been observed in a variety of wave phenomena, including pulses of light traveling in optical fibers, ocean waves, and in many other diverse phenomena, perhaps even in the collective oscillations of protein and DNA molecules. The largest known soliton-like object is the Great Red Spot on Jupiter.

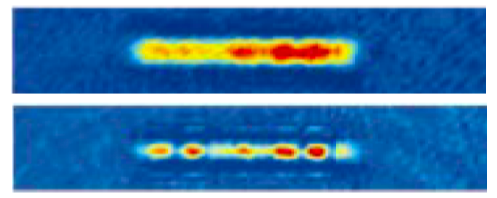

Figure 1: Rapidly quenching the interactions to be attractive can change a single, elongated condensate with repulsive interactions (upper image) into a soliton train (lower image).

We study matter-wave solitons, which are much rarer, and also exhibit a rich array of phenomena. Quantum mechanics tells us that matter can exhibit wave-like or particle-like behavior, depending on the circumstances. Perhaps the most exotic are collective matter waves known as Bose-Einstein condensates consisting of millions of atoms cooled to near absolute zero temperature, where the atoms act in unison and behave as if they had a common purpose. In order to form matter-wave solitons, we use a Feshbach resonance to change the atom-atom interactions from strongly repulsive, as required for a condensate, to slightly attractive, as needed to form a matter-wave soliton. By forming a single, elongated condensate with repulsive interactions (upper image) and rapidly quenching the interactions to be attractive, a train of solitons (lower image) is formed. Depending on the rate at which we vary the interactions and the geometry of our confinement, we can form anything from a train of up to 10 solitons, to just a single one. We study soliton collisions by creating a soliton pair, separating them to the opposite sides of a one-dimensional harmonic confining potential, and letting them go. They collide at the center of the potential with well-controlled energy.

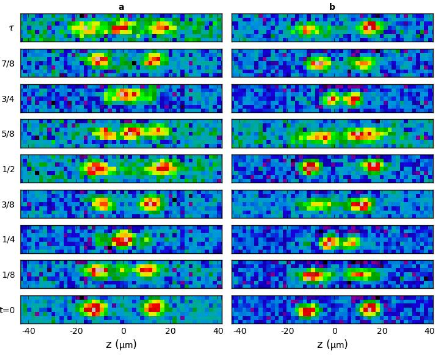

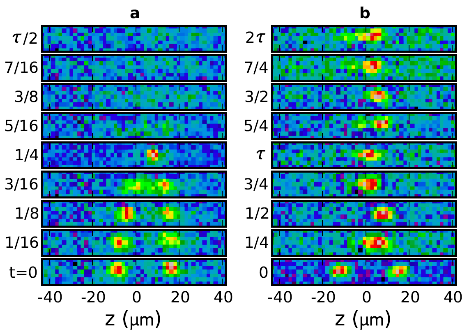

Figure 2: (a) Time evolution showing a full period (32 ms) of oscillation in the harmonic trap when the solitons are nearly in-phase. At the 1/4 point, the solitons collide at the center of the trap (z = 0 μm) and appear to merge. Afterwards, they pass through one another before colliding again at the 3/4 point. (b) Similar to (a) except for the case when the solitons are nearly out-of-phase. At the 1/4 and 3/4 points, the solitons appear to be separated by a small gap, after which they appear to bounce off each other.

Theory tells us that solitons don’t interact during a collision, but rather pass through one another without change in velocity or amplitude. Since solitons are waves characterized by an amplitude and a phase, they may interfere with one another giving the appearance of a soliton-soliton interaction.

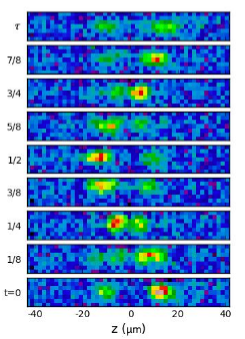

When the solitons have the same phase (a), they interfere constructively during the collision giving a density peak (anti-node) between them, visible at ¼ of an oscillation period. The solitons separate, and subsequently re-collide at ¾ period since they are harmonically confined. When solitons are out-of-phase (b), they interfere destructively, leaving a node in the density between them. This node gives the appearance that the solitons bounce off each other. A natural question is: how can we tell if they’re repelling or passing through one another? An intuitive way to see this, is by ‘tagging’ the solitons, by making one smaller than the other. In the figure on the right, we can clearly see the smaller soliton passing through the larger one while maintaining a gap between the two during the collision.

Figure 3: Time evolution showing a full period of oscillation (32 ms) with tagged solitons that are nearly out of phase. At the 1/4 and 3/4 points, the solitons maintain a minimum gap between them during the collision. Afterwards, we observe that the solitons pass through one another as they did in the nearly in-phase case.

An interesting thing can happen when the strength of attractive interaction between atoms is increased. For in-phase collisions the density spikes during a collision, and the strength of the interaction can become overwhelming resulting in complete annihilation (a), or in other cases, they may merge (b).

Ongoing studies into collisions between solitons provides insight into non-equilibrium dynamics of nonlinear systems, and is an important stepping stone towards exploring how solitons can be made into an interferometer, much like a matter-wave version of a laser gyro.

Figure 4: Time evolution showing a full period of oscillation (32 ms) for nearly in phase solitons. After colliding, we have observed complete annihilation (a) and mergers (b) occurring.

Reference

[1] “Collisions of matter-wave solitons”, J. H. V. Nguyen, P. Dyke, D. Luo, B. A. Malomed, and R. G. Hulet. Nature Physics 10, 918-922 (2014).

[2] “Interactions of solitons with a Gaussian barrier: Splitting and recombination in quasi-1D and 3D”, J. Cuevas, P. G. Kevrekidis, B. A. Malomed, P. Dyke, andR. G. Hulet. New Journal of Physics 15, 063006 (2013)

[3] “Bright Soliton Trains of Trapped Bose-Einstein Condensates”, U. Al Khawaja, H. T. C. Stoof, R. G. Hulet, K. E. Strecker, and G. B. Partridge, Physical Review Letters 89, 200404 (2002).

[4] “Formation and Propagation of Matter Wave Soliton Trains”, K. E. Strecker, G. B. Partridge, A. G. Truscott, and R. G. Hulet, Nature 417, 150 (2002).